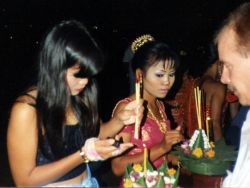

When the tide is high and rivers brim on the full moon in November, Thais pay tribute to water. Held every year in the night on a full moon of the twelfth month of the moon calendar, the Loi Krathong festival sees most of the population head to canals, streams or rivers like the Ping or Chao Phraya to bless this element so central to their culture, and to seek forgiveness for using and polluting it in the process. Thais say this thank you with flowers. Only we don’t present bunches or even garlands; we fit the plants architecturally into krathong — elaborate natural rafts that they construct from materials found in the traditional Thai garden or field. Most urbanites, however, buy ready-made krathong from pierside stalls.

What is a Krathong?

What is a Krathong?

Unlike offerings to altar, vehicle or shrine, a krathong needs to loi (float), so they’re made of nature’s Styrofoam: slices of yuak gluay (banana trunk). Environmentalists and traditionalists have fought recent attempts to substitute plastic Styrofoam, and have largely kept the festivities green. In a contemporary compromise, inventive souls now bake multi-colour dyed bread krathong to subsequently feed the fish and turtles, though the crust makes it hard to pierce with pins or flower stems. Two-inch slices of yuak kluay provide better buoyancy and fibrousness for attaching the decoration, which is suffused with auspicious meaning. This miniature vessel embodies many levels of Thai arts and beliefs, helping to keep the craft skills alive.

Leaf origami

This time of year, the country’s banana trees get shorn of their most pristine leaves (bai tong). Over a meter long, they are de-spined and spliced into square sections suitable for cutting out to wrap the float and to fold into shapes derived from lai thai — the intricate patterns that form a symbolic language seen throughout temples, palaces and traditional arts.

Around the edge, nimble fingers are required to pleat blades of tang maprao (coconut leaves) into boxy geometric protrusions that come to resemble an open lotus pad. Bamboo pins keep the origami under tension in case it springs undone.

On top rises a lotus bud shaped spire built of bai tong. At its core, a chedi (stupa) shaped cone of leaf typically contains cooked sticky rice. The rice not only symbolises a staple derived from aquaculture, but its broad-based weight steadies the raft and its glutenous mass secures the myriad pins attaching the pointed side decorations. Called jeeb krathong (splayed leaves), the decorations evoke the jeeb finger gesture intrinsic to Thai dance. Tipped with dok phud (white jasmine buds), these sprays of twisted banana leaf also get dubbed nom maew from their resemblance to cat’s nipples.

On board the raft you find various lucky flowers, though none with negative connotations like lan thom (frangipani), which sounds like the term for sorrow. Dok bua (lotus buds) are most prevalent, along with yellow dao reuang (chrysanthmum), red dok kulaab (rose) and baan mai rue roy (globe amaranth), a bristly, non-wilting bloom that comes in white or purple. Orchids — sometimes dyed with even brighter hues than nature intended — are increasingly common stow-aways.

Completing the offering are the requisite candle and triple sticks of incense of Buddhist worship. Since the idea has arisen that you can wash your troubles away on launching your krathong, many Thais place a tiny piece of themselves — such as a hair or nail clipping — into the craft, along with a coin for good fortune.

Historic symbolism

With its central spire and decorative points at four cardinal points, a krathong can be seen as a mini Mount Meru. Stylisations of this sacred abode of the gods resonate throughout Thai royal and religious iconography. This Hindu heritage is also seen in the identity of the worshipped water goddess, Mae Khongka, who translates as Mother Ganges. The festival falls close to the Hindu festival of lights, Deepavali, and krathong likewise appear like tiny lanterns, with their candles and incense embers twinkling as they bob downstream. The compound effect of dozens, hundreds, even thousands of such lights draws many a sigh at the redemptive power of beauty.

Nang Noppamat

Legend has it that princess Nang Noppamat at the court of Sukhothai, the first independent Thai kingdom, initiated the ritual of Loi Krathong. Eight centuries later, the national focus that night falls on the reflective ponds at Old Sukhothai’s ruins. There fireworks and son-et-lumiere shows spotlight outsized artificial krathong acting as centerpieces to the ponds where thousands of devotees each float their krathong.

The ngan wat (temple fairs) that accompany this joyous period nationwide typically include beauty contests to crown a live Nang Noppamat. The pageants act as heats for would-be Miss Thailand contestants, and provide an embodiment of ideal femininity for festival parades and ceremonies.

In

Yipeng At the related festival of Yipeng in Chiang Mai, northerners launch the airborne equivalent of a krathong. Khom loi (floating lanterns) comprise a paper balloon with a burner lit below the narrow opening at its base. Teams of participants hold the bag while the air expands inside, until it surges aloft. Frequently trailing a firework it joins countless other khom loi to create a man-made firmament on a night when moonbeams occludes real starlight. Awed by the spectacle, people launching khom loi don’t so much wish upon a shooting star, as upon a floating star. Thai faith is all about slowing things down to a pace where one can contemplate.

Yipeng At the related festival of Yipeng in Chiang Mai, northerners launch the airborne equivalent of a krathong. Khom loi (floating lanterns) comprise a paper balloon with a burner lit below the narrow opening at its base. Teams of participants hold the bag while the air expands inside, until it surges aloft. Frequently trailing a firework it joins countless other khom loi to create a man-made firmament on a night when moonbeams occludes real starlight. Awed by the spectacle, people launching khom loi don’t so much wish upon a shooting star, as upon a floating star. Thai faith is all about slowing things down to a pace where one can contemplate.

© Royal Flora Ratchaphruek